Digital butler or spyhole? What you need to consider when implementing a tenant app

For tenants, they alleviate many of the processes that occur during the course of a rental relationship both regularly (e.g. paperless receipt of utility statements) and occasionally (e.g. straightforward reporting of any defects or damage to the landlord), and landlords also enjoy a host of benefits. For example, they can select and commission the required craftsmen via the app at short notice or manage all administrator information digitally.

The above examples show that vast amounts of personal data, in particular for tenants, is collected, processed and distributed digitally. The information saved includes the specific address at which tenants live, when they reports defect and what faults occur in the apartment they are renting, but also how high their utility costs are and when and how much is paid.

All these details are classes as “personal data” according to the German Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz; BDSG), i.e. individual information about a natural person’s personal or factual circumstances. This data is subject to extensive protection. For example, as early as 1983, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled the following in the “census verdict”:

“Under the conditions of modern data processing, the protection of individuals against unrestricted collection, storage, use and disclosure of their personal data is covered by the general right of personality of Art. 2 Sec. 1 in connection with Art. 1 Sec. 1 of the German Constitution. To this extent, the fundamental right guarantees that individuals have the power to make their own determinations about the disclosure and use of their personal data.”

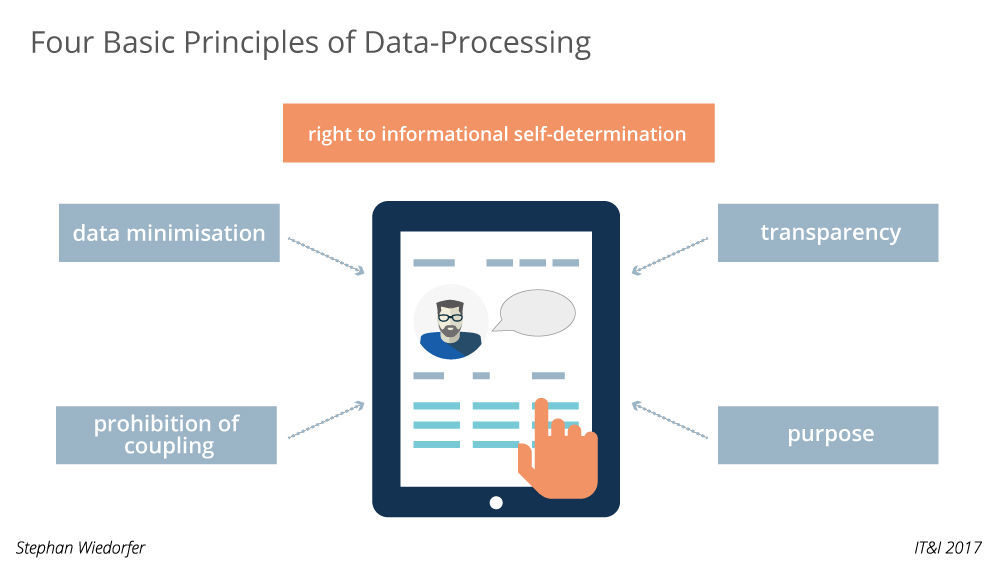

This “right to informational self-determination” has the character of a fundamental right.

It goes without saying that the collection, compilation and, in particular, analysis of all data relating to a rental relationship could result in a comprehensive and useful user profile for each tenant if the tenants in question use the app and said app does not observe the data protection specifications. Even more so if the app is also linked to additional external services, such as pizza delivery services or sales and evaluation platforms. The extensive analysis and use of the collected information would, for example, make it possible to target the tenant in question with specific advertisements that are precisely tailored to his or her requirements and user behaviour.

To prevent such apps from “spying on” tenants on a large scale and using the information improperly, you must therefore ensure that tenants have the right to determine for themselves what happens to their information. Specifically, the data-processing entity must comply with four basic principles (Figure 1).

Figure 1: When collecting personal data within a tenant app, four important data protection principles must be complied with.

Figure 1: When collecting personal data within a tenant app, four important data protection principles must be complied with. |

The first principle of data protection is “data minimisation”. The German Data Protection Act requires as little personal data as possible to be collected, processed and used. Accordingly, tenant apps must collect no more data than is required for the specific purpose. To remain with the above example, storing the tenant’s eating habits would not be permitted, as this is not needed to implement the tenant relationship.

A further data protection principle that must be observed is the “prohibition of coupling”, which means that data can only be collected within narrow limits in relation to providing a service. For example, only allowing tenants to use a particular app if they first agree to the use of their personal data for address trading or advertising would not be permitted.

In addition, the principle of purpose must be ensured, meaning that the landlord is permitted to use the tenant’s personal data only for the specifically designated purpose (in this case for handling correspondence between the tenant and the landlord) and this data must be deleted once the purpose has been fulfilled. Otherwise the landlord could pass this information on to third parties illegally for a high price, for instance. However, he or she would also receive personal information regarding tenants that have nothing to do with the intended purpose and that are also not necessary for this; for example, the tenant’s culinary preferences.

Finally, the principle of transparency ensures that tenants must be informed about the saving of their personal data, and, in particular, the manner, extent and purpose of saving such data. It is therefore essential that tenants receive an overview of which specific personal data will be saved and processed before they even use a tenant app.

As in most cases the personal data collected via tenant apps is ultimately processed by external service providers, this is also a case of commissioned data processing. In this regard, § 11 BDSG clarifies that the “responsible party” for the personal data remains the landlord, even if the landlord makes the data available to third parties for appropriate preparation and processing. The specified provision regulates the requirements for this kind of commissioning of data processing by third parties and aims to ensure that only the landlord makes decisions regarding the collection, processing and use of the data.

A tenant app must therefore observe these extensive data protection specifications if it is to be permissible and capable of sensibly supporting the respective interests of tenant and landlord.

Author:

Stephan Wiedorfer-Rode

was born in 1967 in Munich. He studied law in Munich and, during his traineeship, worked in New York for six months for Germany’s largest record label. He has been a member of the bar since 1996 and founded his first law firm in 1999. He specialises in consulting in the field of computer and Internet law, including procedural enforcement of the relevant claims. His other areas of activity include trademark, copyright and competition law. Stephan Wiedorfer has been a certified specialist for industrial property rights since 4 February 2008. He is a member of the Deutsche Vereinigung für gewerblichen Rechtsschutz und Urheberrecht e. V. (GRUR; German Association for Industrial Property and Copyright), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Recht und Informatik e. V. (DGRI; German Association for Law and Informatics)) and the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Informationstechnologie im Deutschen Anwaltverein (DAV-IT; Information Technology Working Group of the German Association of Lawyers).

Other articles by this author:

- Article "Compliance – what is actually still permitted today?"

- Article "Is the Internet of Things first and foremost an Internet of legal uncertainty?"

- Article "There was once a noticeboard... How to use social media channels in a legally compliant manner"

- Article "Digital butler or spyhole? What you need to consider when implementing a tenant app"

- Article "Contract design for software implementation – how significant are fairness and transparency?"

- Article "Everything is flowing smoothly – drafting contracts for agile projects"

- Article "WhatsApp in companies – how can it be used in a legally compliant way?"

- Article "What digital data rules are in place for asset and property management contracts?"

- Article "Smart, sure. But safe? Drones deployed for property management"

- Article "Are security vulnerabilities to hacker attacks a defect for which the software provider can be held liable?"

- Article "Gas prices are rising and the gas price cap is intended to remedy the situation."

- Article "Landlord-to-tenant electricity – a sustainable energy alternative"