What is new in the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)?

New information obligations for the collection of personal data

Even today, extensive obligations to inform those concerned must be met when collecting personal data. These transparency obligations arise from the German Federal Data Protection Act and, in particular for telemedia such as apps and websites, from the German Telemedia Act. These are now supplemented by Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR. What is new here is the specification of the legal basis for processing the data that has to be presented to those concerned. In the past, those responsible for a website only had to describe the purpose of data processing in an easily comprehensible way. The new challenge now is to present the legal basis in an easily comprehensible way too, as well as the purpose. If, for example, you wish to record a tenant’s address for the purpose of establishing contact, in addition to specifying this purpose you must also specify the legal basis that permits the address to be saved. Depending on the scenario, Article 6 Paragraph 1 lit. b) may be appropriate here. This would permit the address to be processed in order to fulfil a contract.

Alongside specifications regarding the period for which the personal data will be stored, a reference to the right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority and specifications regarding profiling, it is also necessary to provide information regarding the new right of data portability. The primary intention of this right was to allow users a smooth transition between social networks and to provide users with transparent information regarding the data about them that is saved. Basically, the right to data portability applies to all those responsible for processing a user’s personal data. In future, data should be exchanged directly between two responsible parties, assuming this is technically feasible. What is not defined is who classifies the “technical feasibility”.

The new “right to be forgotten” and changes of purpose

The principle of the “right to be forgotten” is similar to

that of the current Federal Data Protection Act, namely that personal data for

which the purpose of storage has expired, which is processed inadmissibly or

for which the person concerned demands deletion must be deleted providing this

is not prevented by any archiving obligations or other regulations. What is new

here about the “right to be forgotten” is simply the broad validity for the

entire European Union and the associated financial penalties that are imposed

if the personal data is not deleted or is even processed illegally. The GDPR

contains simplifications for the change of purpose, which are laid down in

Article 6 Paragraph 4. For example, it is now possible to

additionally safeguard the data records using technical measures in order to

process them for further purposes. However, this requires detailed

verifications of the rights of those concerned and documentation of the

intention beforehand.

The privacy impact assessment

The principle of the technology impact assessment is not new. What is new, however, is that this procedure has to be applied in the context of data protection. As part of a privacy impact assessment (PIA), each company must assess the consequences for those concerned when processing personal data if new technologies are used or if the manner, scope, circumstances and purpose of processing are such that they will probably give rise to a high risk for the rights and freedoms of natural persons. Here, the data protection supervisory authority has the possibility of publishing lists of the processes for which it is imperative to perform a privacy impact assessment. The content and requirements to be taken into account are described in Article 35 of the GDPR and provide a picture of the approximate scope of such an assessment. For example, a privacy impact assessment must always be performed when monitoring publically accessible areas using optoelectronic devices – in other words video surveillance – as this involves a high risk for the rights and freedoms of those concerned.

Rules of conduct and certification

The previous Federal Data Protection Act lacks foundations for uniform certification and voluntary commitment to rules of conduct regarding data protection. The new rules laid down in Articles 40 to 43 therefore provide reason to hope for additional transparency regarding adherence to data protection rules. Here, supervisory authorities in particular are required to play a part in elaborating rules of conduct and introducing privacy-specific certification procedures, data privacy seals and marks of conformity.

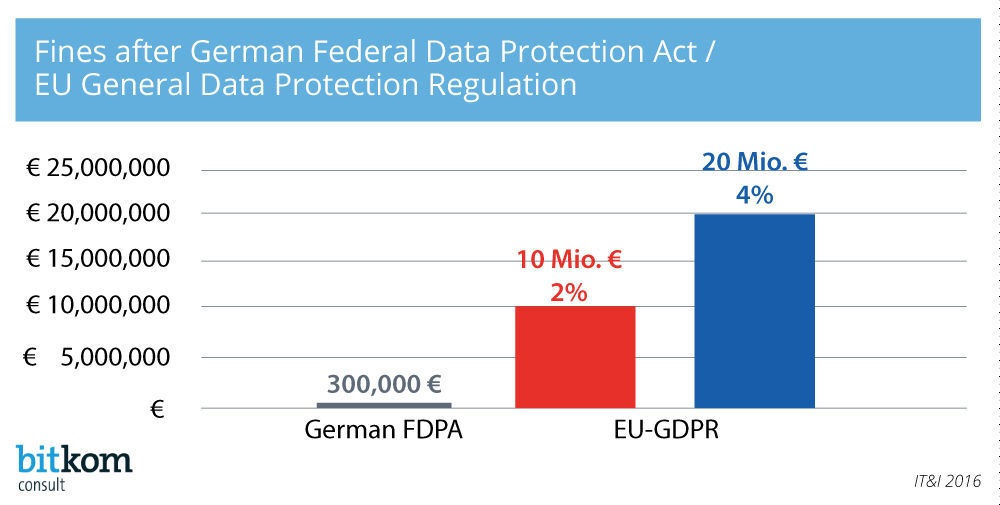

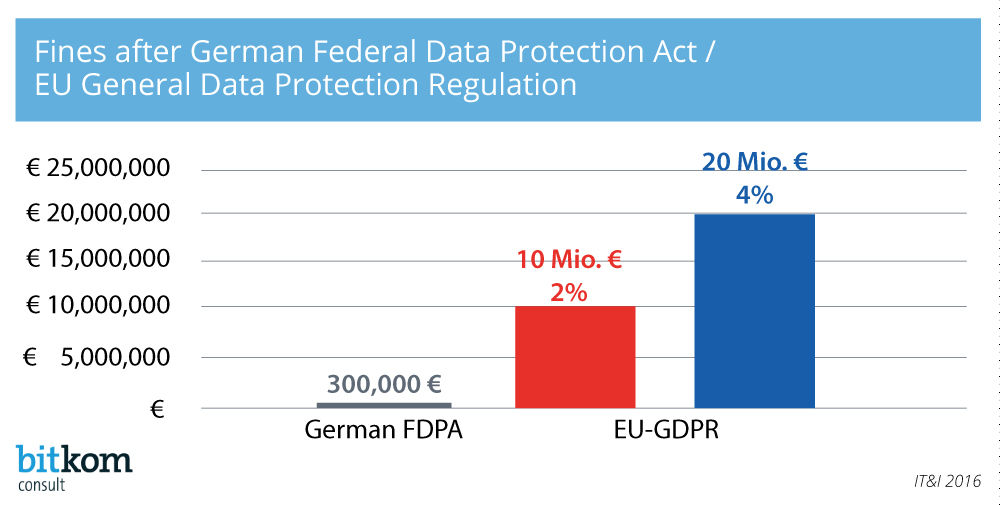

Liability, sanctions and compensation

The area of liability and sanctions is described in Section 8 of the GDPR. What particularly stands out here is the increase in financial penalties compared with the Federal Data Protection Act. The Federal Data Protection Act stipulates a maximum of EUR 300,000 per violation, while the General Regulation specifies EUR 20,000,000 or four percent of the total annual sales recorded worldwide in the past fiscal year. The possible sanctions therefore certainly have a deterrent effect.

Figure 1: Comparison of the financial penalties as per the Federal Data

Protection Act and EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). |

Summary

It remains to be seen what corresponding national legislation will be

enforced and how opening clauses will be defined here. The opening clauses will

in no way permit any circumvention of the GDPR, though. Instead, they should be

understood more as options or more precise specifications that will be anchored

in a subsequent version of the Federal Data Protection Act. It also remains to

be seen how quickly the supervisory authorities will be able to satisfy the

numerous new rules. However, no company should wait. There are only just under

two years left until the General Data Protection Regulation takes effect.