Talk to one another! The Internet of Things is making building services speak

…if you can

However, when you get closer to the forest, you learn to distinguish the various different trees from one another. One is happy to chat away, regardless of who is listening, while the other is very selective about what to disclose, and to whom. Other trees may only want to talk to their own kind, and then there are groups who have communicated among themselves in their own dialect and work hard to get other trees to join their club, with varying degrees of success.

The “Internet of Things” is not the long sought-after harmonisation of all communication standards that so many are hoping for. The “Internet” simply promises that a common infrastructure will be used, which could potentially allow global reachability. A series of rules ensures that messages reach their destination intact and do not get in each other’s way if possible. The actual user data can take various different forms. It might be a self-explanatory plain text, such as the word sequence “light on”, while for another system, it could be an encrypted command set, which recipients can only decrypt if they have the right key. This is all reminiscent of a parcel service that takes care of sending all sorts of different parcels, without knowing anything about their contents. So whether two devices can communicate with one another meaningfully does not depend entirely on their Internet connectivity; it comes down to whether they speak the same language.

The choice is vast. The best thing to do is take a look at the various wireless protocols (of which there are around a dozen) vying for the attention of device manufacturers and users in the area of building services. The front-runners at present are Z-Wave and ZigBee, which each have major alliances with numerous manufacturers behind them. They both promise to collaborate smoothly with devices from the same camp. This promise is usually also fulfilled reasonably well. The most well-known example at present is probably a system of LED light fixtures in the shape of light bulbs designed for private housing, which communicate with one another via ZigBee and can be operated conveniently using ZigBee-enabled light switches, via a WLAN bridge or using a smartphone app.

Shining examples

Lights are the first thing that comes to mind when

looking for potential candidates for IoT in buildings. Of all the technical

systems, they are the most abundant and most evenly distributed. Major lighting

manufacturers have already implemented this realisation in products: LED

ceiling lights with just an Ethernet connection and no power connection. The

LEDs are content with the power supplied to them in the form of Power over

Ethernet. The purpose of the data connection is to read out the sensors built

into the lights or even to modulate information to the light in the opposite

direction at a high frequency in a way that is invisible to the eye. A

smartphone with a camera and the appropriate app retrieves information from

this matching the location of the lights. These kinds of systems are already in

use in museums and shopping centres.

Tenuous security

The communication capability of IoT devices is the prerequisite for using their data for a range of services. At the same time, it is also a curse, as the information intended for the actual recipient of the message can also be followed by unauthorised eyes and ears. The wireless solutions, which are especially popular for retrofits, make things particularly easy for the bad guys: wireless signals are easy to intercept. Although there are serious approaches for encrypting wireless communication, manufacturers are often sloppy when it comes to implementation or make it too easy for users to start up devices and systems without at least setting an individual password. Wirelessly-controlled garage doors, Bluetooth door locks or radiator thermostats can often be hijacked with alarming ease.

Security is

all the more important when the building system goes beyond the home into the

Internet, for example for invoicing or maintenance purposes. Three years ago,

the remote maintenance function of a major heating system manufacturer made the

headlines for the wrong reasons in relation to this, which were only silenced

when the manufacturer recommended that users literally pull the plug on their

systems. A few months ago, it was revealed that even alarm systems can be

outsmarted with relatively simple means and are thus more beneficial to

burglars than property owners.

Dull prospects

Even if all the gateways are closed and all security functions activated, the question remains: To what extent does user data develop a life of its own once it leaves the home and heads to the cloud? It is not difficult to use the data from motion detectors and utility meters to reconstruct the times when an apartment is empty and when someone is at home. In the wrong hands, this is useful knowledge for planning the next attack. In times when the customer databases of online shops are being hacked by the dozen, or bitcoin bank robbery is experiencing an upsurge, this is not a far-fetched scenario.

Yet some providers of smart home systems are unperturbed in their readiness to connect home installations to the manufacturer’s servers. If set up if intelligently, then at least the local installations continue to run if the connection to the server fails; if not, the failure will literally result in a cold shower, because the boiler will no longer work.

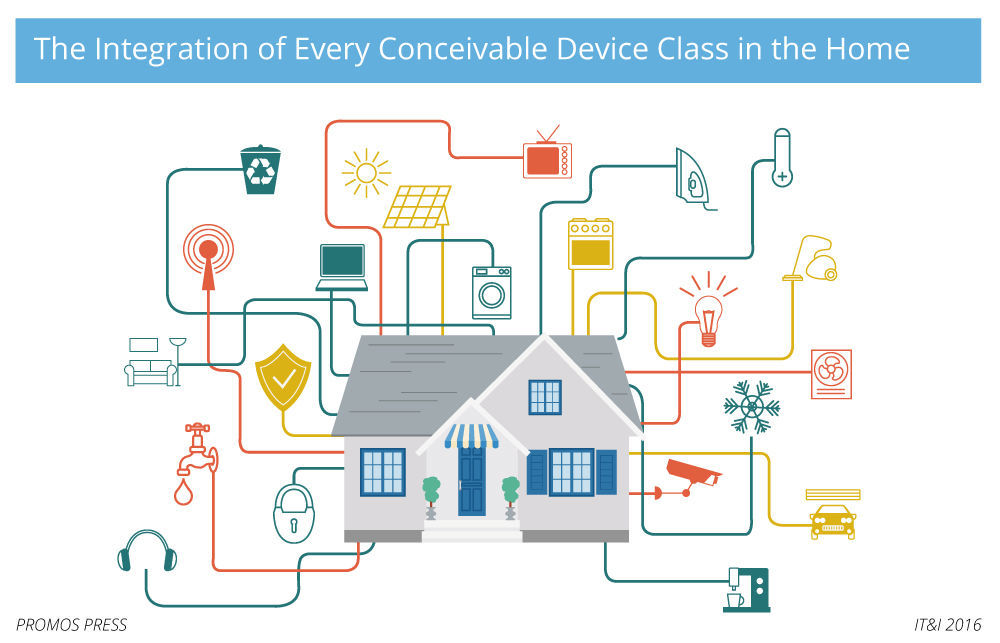

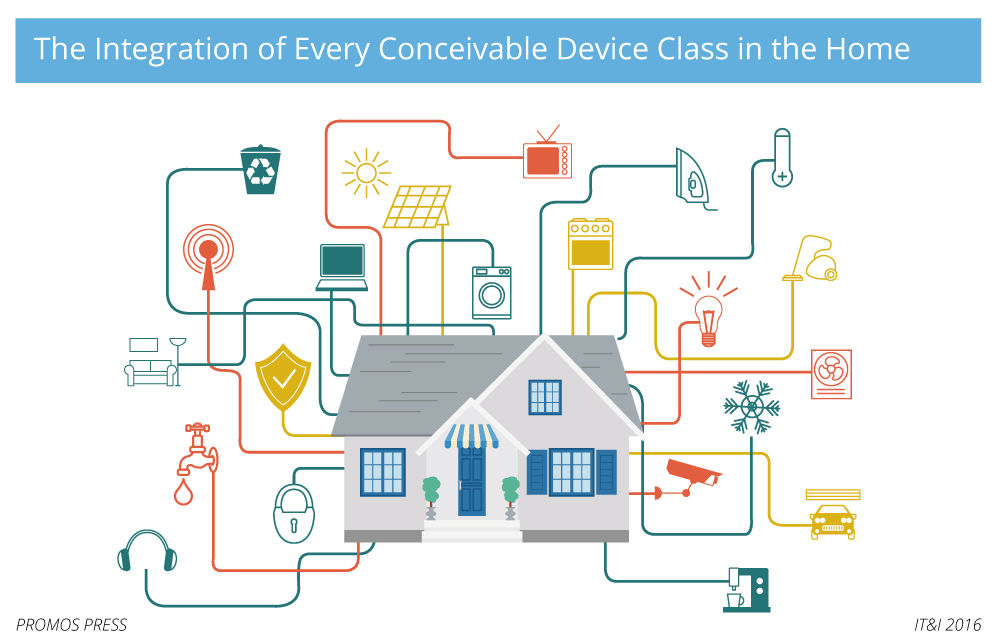

Figure 2: Many smart home providers promise to integrate every

conceivable device class in the home. However, this requires a

connection to the system provider’s server. |

Reluctant customers

For providers of smart measurement or automation systems, the large housing companies would be ideal, as they are profitable customers. However, they have their own, cautious perspective, and for good reason. From the viewpoint of their facility management, it would certainly be useful to be able to collect highly precise spatial and temporal data consumption data for settlement purposes. Yet they are usually faced with a very heterogeneous measurement landscape in real estate structures that have evolved over decades, which could only be updated in line with current standards with immense effort.

To add to this, various studies and pilot projects have confirmed the hard realisation again and again that the average tenant household is far from as enthusiastic about all the new options for controlling their home technology as the manufacturers would like to make out. The impact of this is just as clear to see when it comes to the perceived user comfort or savings, and when weighing up the costs and benefits, a decision against full-scale implementation of the technology in question is frequently made.

There is still a long way to go before the “Internet of Things” breaks into mainstream building technology. With the exception of some useful usage scenarios, there is still a lack of understanding as to what the point of it all is. The effort required for implementation and maintenance seems disproportionately high and, not least, newly discovered security gaps urge caution again and again.