Is the Internet of Things first and foremost an Internet of legal uncertainty?

It is clear that this type of technical advancement, in particular, raises a host of legal questions. Just consider that in the future, for example, my fridge will know when and with which products I fill it and when and in what quantity I take things out and consume them. After all, the myriad data that is collected in this process is not taken solely for self-serving purposes (e.g., to regulate the cooling power), but primarily in order to father vast amounts of data regarding my personal eating and consumption habits. Ultimately, this is used to create an extensive and detailed model of my behavioural patterns and thus obtain high-quality information regarding my eating habits as well as the purchases I make.

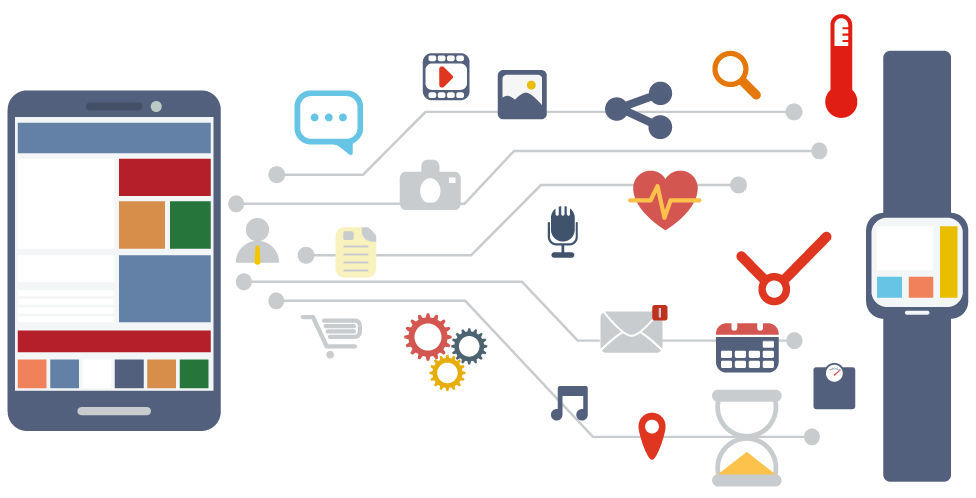

Of course, this data is a valuable asset – after all, it allows the recipient to offer me specific goods that are individually tailored to my requirements and consumption, for example. But even the watch on my wrist, which supposedly only records my pulse, collects much more extensive, highly sensitive and personal data that not only maps the full state of my health, but also creates an accurate pattern of my movements with a precise breakdown of when and where I went and, in particular, my body’s readings at this particular location.

In search of legal standards in the data protection jungle

These examples illustrate that data

protection is a key legal aspect of IoT, and if we take a closer look at the

regulations up to now, it is clear that many things indeed remain unregulated,

as the current scope of data protection is much too narrow for these technical

challenges. In particular, the regulations do not take into account the fact

that autonomous communication takes place exclusively between objects without

any involvement from humans, and that, in the course of this communication, a

host of data is produced that is recorded in various different places, whereby

it is entirely unclear who has access to this data when and how. In particular,

the question arises regarding which legal subject records this data. This

information is of fundamental importance under current data protection law, as

only this subject is and can be the addressee of legal norms, and not “the

things”. Furthermore, the current principle of data minimisation (i.e. the

specification that only a minimum of personal data should be saved) also

contradicts the Internet of Things, which this thrives on precisely this mass

of data, as well as on recording the data and its availability. The exchange of

data between the individual communication points themselves and the scope of

protection to be considered have also been completely unregulated up to now.

Moreover, when adapting the data protection requirements, it is also necessary to consider that data glasses, for example, are theoretically capable of recording and storing all the people in their field of vision, so even those who have consciously chosen not to use “wearables” are ultimately being observed systematically and can also be made the subject of movement profiles. Thus, a simple walk through a pedestrian zone affects the data protection requirements of hundreds of people. Although the existing data protection legislation provides starting points, as it permits the recording of personal data only in very specific exceptional cases, the question is still: Who is actually responsible for recording this data? It is unlikely to be the person wearing the glasses, who is neither interested in the recorded data nor even aware that data is being recorded and analysed fully automatically. If the constitutionally protected rights of each individual citizen cannot be legally safeguarded, in extreme cases, this could theoretically even lead to a ban on these types of data glasses.

Who is in charge of the data?

But

even basic legal issues have not been clarified at all up to now: for example,

who the actual actors are when it comes to the Internet of Things remains

unclear. According to our legal system, only people or legal entities can hold

rights and obligations. However, how does this apply if decision-making

processes are fully automated; for example, if the fridge autonomously decides

to have more milk delivered because I am running low? In this case, have I actually

made a decision that can be attributed to me? If not, who can this decision be

attributed to and why? What happens if errors occur in this process, such as

the wrong milk being delivered? All of these basic questions need to be

answered in order to create legal certainty. If you then also consider that,

for example, statutory regulations regarding the conclusion of contracts via

e-mail took several years to be incorporated into the German Civil Code

(Bundesgesetzbuch, BGB), it is clear that the development of legislation will

very soon be lagging behind given the rapid rise of IoT.

Another question that has not yet been clarified and is currently the subject of hot debate relates to ownership of the collected data. Who should this data belong to? Who should have control of it? The individual that ultimately collects it (with the aforementioned problem that this could also be a machine) or the individual that actually causes this data to exist in the first place (i.e. the person who uses the fully automated fridge)? And what about data that is generated solely through communication between two inanimate objects; for example, the temperature sensor and the apartment window, which opens fully automatically to allow fresh air into the room? Here, too, clear legal regulations are required that take into account the economic consequences. One idea that would be worth considering is to share the revenue earned from data collection and analysis between the data collector and the data provider.

Conclusion

We

thus have to conclude that, even for just the small snapshots presented here,

there is considerable need for legislation in connection with the “Internet of

Things” since, in contrast to the “simple” Internet, the existing legal

regulations are not sufficient to solve the problems that are now arising.

Although the public perception still that the Internet is a “legal vacuum”

still partly exists, in reality it must be noted that the legal questions that

arise here could and can largely be clarified based on existing legislation.

However, for the points described above relating to the Internet of Things,

this is currently not the case. Thus, legislators now need to take specific

action to avoid falling behind and causing legal vacuums to arise!

Author:

Stephan Wiedorfer-Rode

was born in 1967 in Munich. He studied law in Munich and, during his traineeship, worked in New York for six months for Germany’s largest record label. He has been a member of the bar since 1996 and founded his first law firm in 1999. He specialises in consulting in the field of computer and Internet law, including procedural enforcement of the relevant claims. His other areas of activity include trademark, copyright and competition law. Stephan Wiedorfer has been a certified specialist for industrial property rights since 4 February 2008. He is a member of the Deutsche Vereinigung für gewerblichen Rechtsschutz und Urheberrecht e. V. (GRUR; German Association for Industrial Property and Copyright), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Recht und Informatik e. V. (DGRI; German Association for Law and Informatics)) and the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Informationstechnologie im Deutschen Anwaltverein (DAV-IT; Information Technology Working Group of the German Association of Lawyers).

Other articles by this author:

- Article "Compliance – what is actually still permitted today?"

- Article "Is the Internet of Things first and foremost an Internet of legal uncertainty?"

- Article "There was once a noticeboard... How to use social media channels in a legally compliant manner"

- Article "Digital butler or spyhole? What you need to consider when implementing a tenant app"

- Article "Contract design for software implementation – how significant are fairness and transparency?"

- Article "Everything is flowing smoothly – drafting contracts for agile projects"

- Article "WhatsApp in companies – how can it be used in a legally compliant way?"

- Article "What digital data rules are in place for asset and property management contracts?"

- Article "Smart, sure. But safe? Drones deployed for property management"

- Article "Are security vulnerabilities to hacker attacks a defect for which the software provider can be held liable?"

- Article "Gas prices are rising and the gas price cap is intended to remedy the situation."

- Article "Landlord-to-tenant electricity – a sustainable energy alternative"